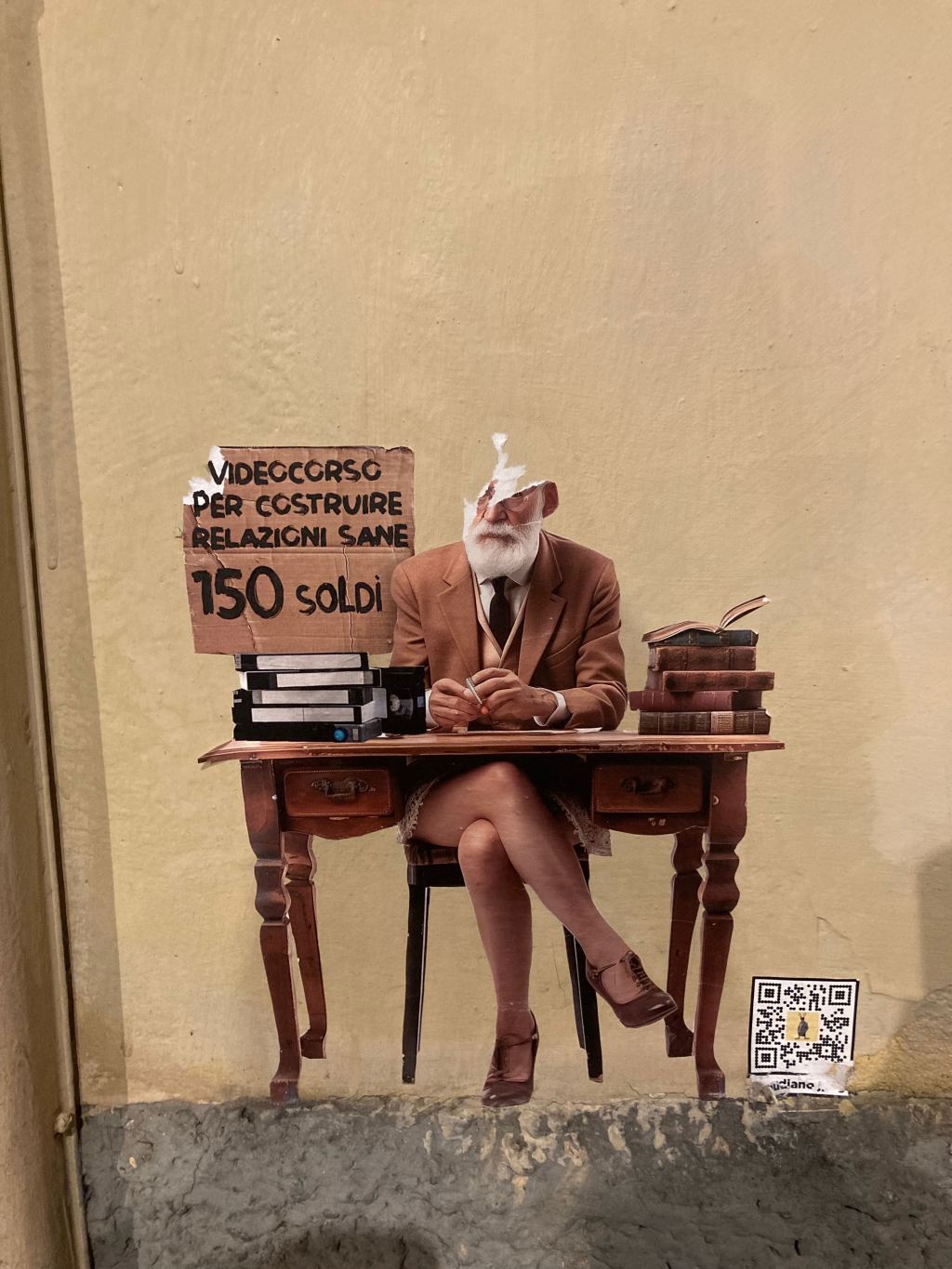

I started thinking about this in my essay on Perfect Days, which is about the alternative hedonism presented by the movie, a vision of life in which commodities are not the center. This picture of some graffiti from my time in Italy reminded me of a central, difficult question about wanting things and what happens when you want things that are unavailable or not easily acquired by money.

We can want things, commodities, as they present us with visions of ourselves as cool or complete or as somehow staving off the reality of finitude. I’m talking here about the things we don’t necessarily need or those objects that fill us with rapturous visions of who we could be rather than satisfying, say, our nutritional needs or our spiritual desires. We can also want things that are not things but are really forms of life: like better relationships; clean air; more kindness; health and happiness for our neighbors. But these things cannot be solved by buying things.

It’s easier to want the thing rather than to want forms of life.

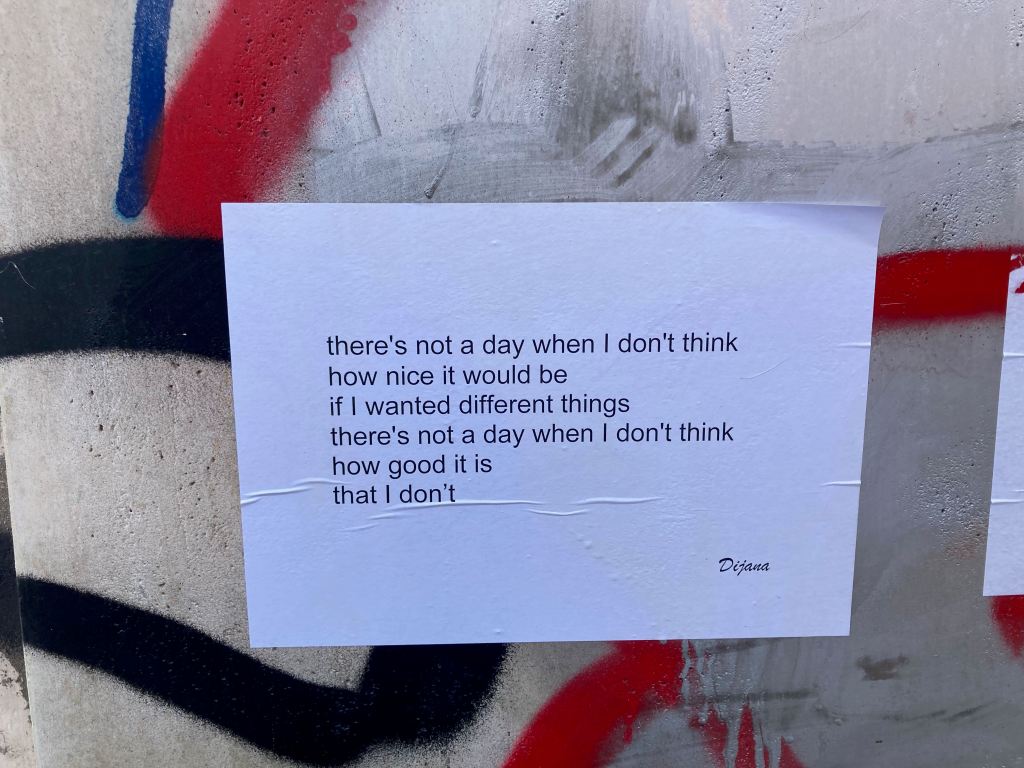

This is why, as Todd McGowan argues, we in some ways like and want capitalism, because it arises from and satisfies things we as humans struggle with and desire. But like Dijana is saying in my photo, things start to get a little difficult when you stop wanting things and start wanting life. (I’ll refer you back to my blog title; less labor, more life!)

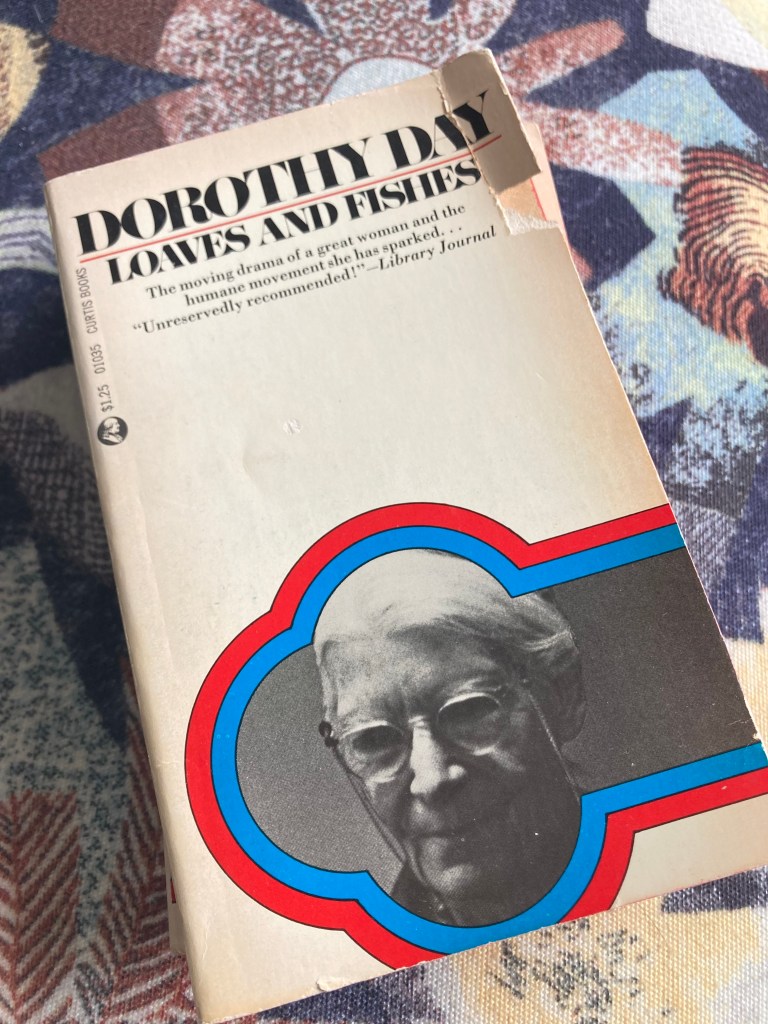

I’ve been thinking about this even more now, reading the memoirs and diaries of Dorothy Day, having become interested in her as a result of Zena Hitz’s fabulous Lost in Thought: The Hidden Pleasures of Intellectual Life. I have always been drawn to the stories of those who follow the difficult path of living what they believe in. And in our moment, it is more necessary than ever, even though Day may roll her eyes at me saying that. She recognized that all moments in history are crisis; not just ours.

The world looks very different if our words and lives come closer into alignment and Dorothy Day’s life demonstrates this powerfully. Her biography is easily accessible, but the two salient details for me are this: that a free, seeking youth lead her to communism and then to Catholicism. Becoming Catholic intensified her commitment to issues of social justice, especially poverty, labor struggles, and anti-war actions. Her life was a practice of living her values fully, in voluntary poverty, caring for the poor, tax refusals, and anti-war protests.

For instance, Day writes an explanation for refusing to pay income tax in Loaves and Fishes, that clarifies .85 on the dollar pays for the military-industrial complex in the US. That was in 1963 when the book was published; I am afraid to confirm my intuition that this number is much higher. After all, in the US when services are cut, that money is almost always directed toward the death machine. By earning less money and consuming less, as the Catholic Workers set out to do, there can be a reduction in complicity with war.

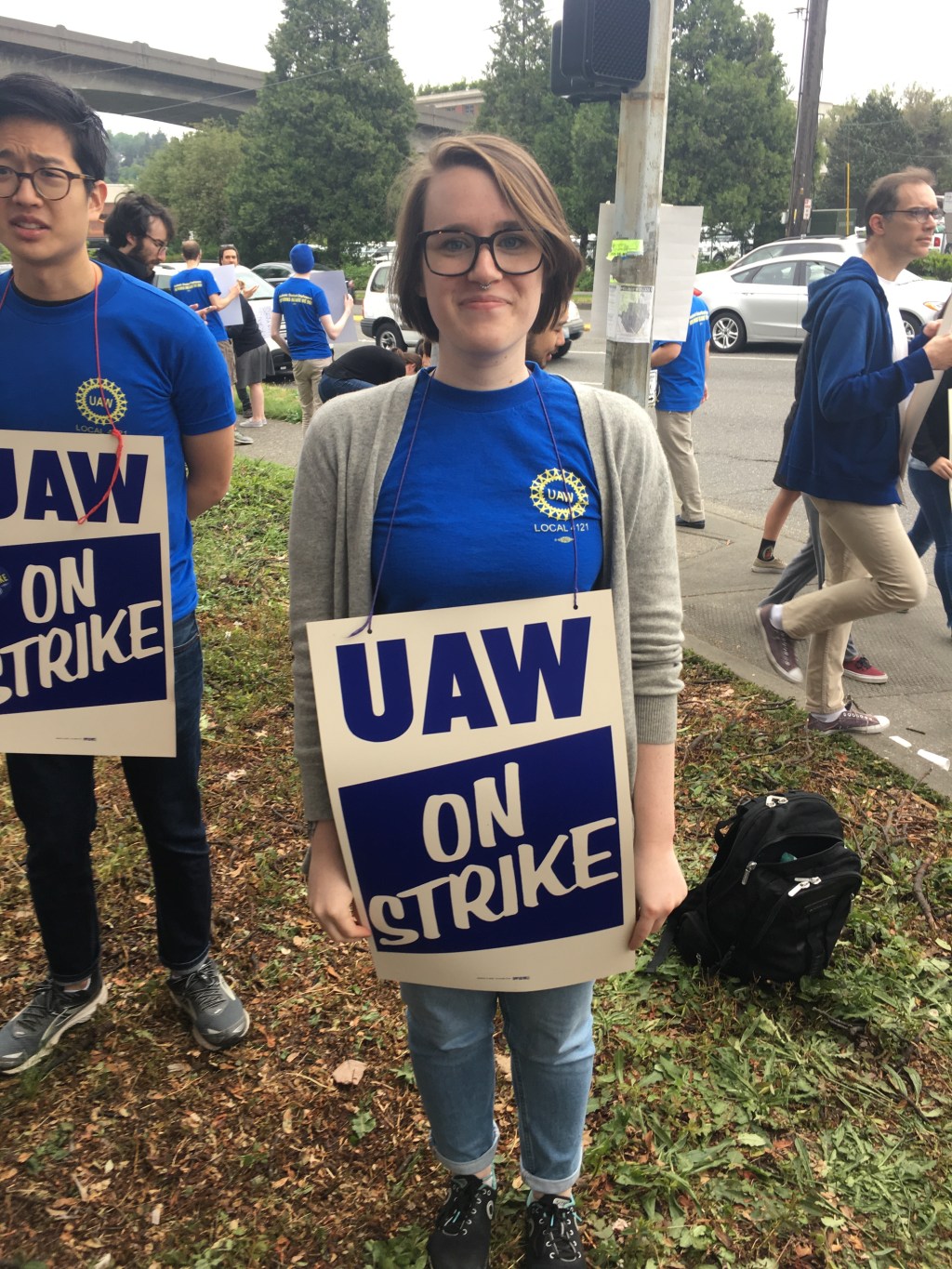

The point is not that we all go out and become Dorothy Day; some of us may become like her but Day would encourage us to work with our desires and our skills toward that vision we have and in community with those who sustain us. Catholicism and anti-capitalist, anti-war politics were central to her vision; her skills were writing, speaking, and caring. For example, I loved parts of being a union organizer; mostly I found it wrecked me every day and I did not have the constitution for it. Instead, I write about how wonderful unions can be and will always participate in one should I have the chance.

This is a principle shared by many of the feminists I read and teach but particularly the Milan Women: following our desire can remake the world. Day emphasized freedom just as much as the Milan Women; it is one of the most compelling aspects of her philosophy. But in a world where our desires are broken and deformed by the market on the one side and the state on the other, what are we supposed to do? How do we find our way forward? I say “we” here because I feel I have been lost in consumer hell myself. I feel like I am becoming aware of how my desires for feminism, love, happiness, community, a better world have been funneled into the only thing available: buying shit!

Across all her work, Day desired, more than worldly goods, a world in which every person has freedom, dignity, care, food, and housing. I find this single-mindedness, something Zena Hitz wrote about recently, so moving. The Catholic concept of vocation is a powerful one. I am not Catholic, but I still, in my 30s, wonder what my vocation is. What is the thing I am single minded about? Feminism? Labor issues? Writing and teaching as many people as possible to tell their stories? Writing novels and essays? The answer, after all, cannot be answered by a force of will.

I think many of us wonder how we can use their special gifts in the world–some of us are even still looking for those gifts, doubting them, chasing them away, hiding if they come knocking. We’ve been taught to love other things besides ourselves and each other, something like Dorothy Day’s life (as she tells us) has revealed to me, loud and clear.

Day’s life, and her life-writing, were so unique, so powerful, I can feel her coming through the pages of her books. To be that alive, to seek life out in the presence of suffering others, amazes me and reflects my life back to me in unsettling ways. The daily courage her life required, well, encourages me. Dorothy Day did not claim the mantle of feminism for herself, but her picture now belongs in my pantheon of spiritual advisers.