At work. I’m supposed to be writing an essay, later to be a powerpoint (that most horrifying of forms), on female freedom, except I can’t write the essay or the presentation because people keep interrupting me. So with my fragmented attention, I scroll through the infinity pool of videos posted by content creators all over the world, looking for videos of women living alone as a kind of research project since I’d recently been tasked with living by and for myself, a sudden change of situation which meant I was naturally curious about what other women were doing. There was something both promising and threatening about this premise. It was as if the sun shone on new possibilities for me in my living while, at the same time, illuminating a void where I had ceased to live at all. In any case, I couldn’t focus on much else besides these videos which required little conscious thought and induced a pleasurable, mind-numbing passivity

In my search, I found mini-films—untouched even by the likes of Godard or Akerman—in which women recorded their daily lives but their faces were always beyond the camera and their voices absent except in scripted subtitles. These formal choices produced a curiously anonymizing effect, exemplified in the automatic translations that captioned the videos, the automatic part leading to slightly awkward English, jarring the viewer out of total union with the image, such as one line that still makes me laugh to think about, a Japanese woman told us that she was “reliably on the sand,” which makes no sense with or without context (could one be unreliably on the sand?). Yet their voices were unique and theirs. I came to know their preferences and habits, felt a certain sense of style in the compositions. Anyway, it was hypnotizing to watch, even the back-and-forth motion between the images on the screen and the captions describing them, revealing the narrator’s feeling and motivation.

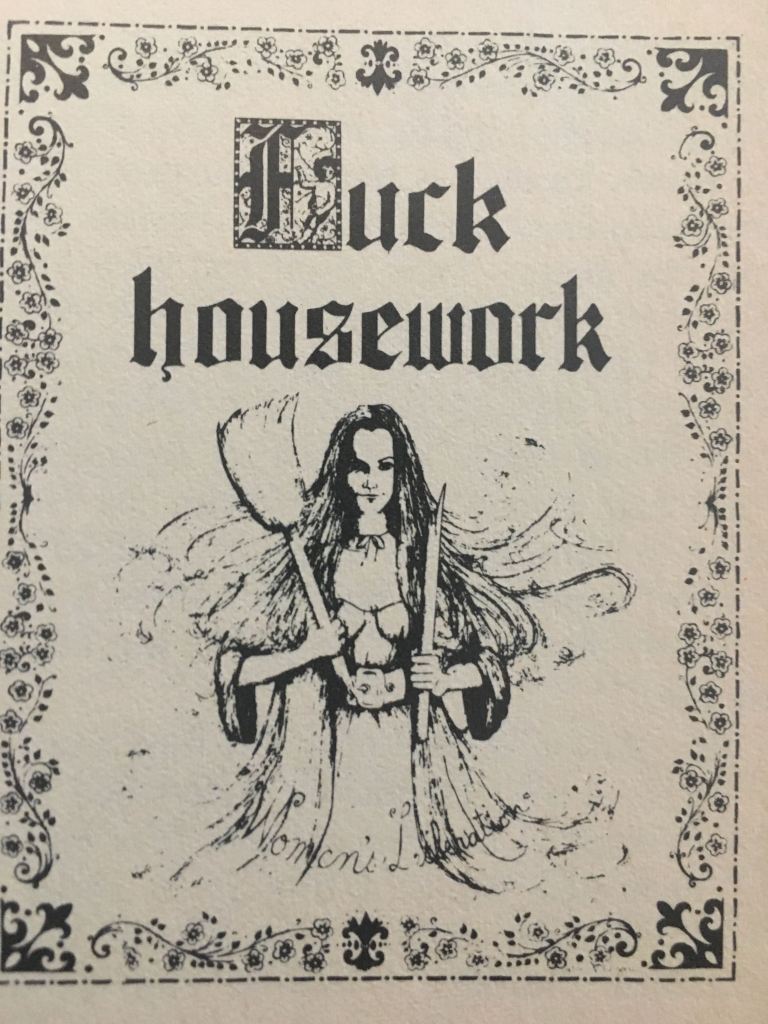

I am moved by a logic of democracy as I watch more and more vlogs, because, unlike the paralysis with which I confront a novel or an essay, in these videos there is no hesitation, no doubt that the recording of one’s own life, no matter how ordinary, was worthy in and of itself, there was no conceit that it was the events demanding representation or recording. The form was motivated by the simple fact of being alive. Here I found a craving for witness that had not compelled these women into partnerships and families but drove them, instead, to broadcast their lives and invite in viewers who may be living alone or, even if surrounded with people, living lonely lives. I, like the anonymous millions watching, could now see, through these vlogs, that daily labor, instead of a discipline imposed by others, could be an aesthetic principle, such an aesthetic visible in the precision of the faceless women’s movements, no aspect of life could be too small to garner attention.

Cleaning ovens

Cooking dinner

Taking a walk

Going to a bookstore

Making art

Getting ready for bed

Doing laundry

Moisturizing one’s hands

The calmness with which life is lived within these frames soothed me. A kind of flat affect prevailed, as the feeling subject in this genre is absent from the camera’s view for the most part and the motions are controlled and precise. The choreography betrayed nothing about the feeling subject except her care with the action right in front of her. A thinking subject is only sometimes referenced in language where she appears, as if by divine revelation, in an expression of pleasure, enjoyment, or exasperation but, as quickly as she bursts forth, obscurity takes hold again and we are, instead, left with poetry of action in which the camera records the mundanity, if not the boredom, of daily life and yet, somehow, aestheticizes (I almost said anesthetized) it, leaving me to wonder how she, any of these faceless and voiceless women, feels. Does she truly enjoy the logistical nature of daily living, of reproducing oneself for the next day, replenishing the body after its depletion for work or does she take her camera to the material in order to satirize, to show the emptiness of life as we now receive it, survival stalking our every moment? That either of these could be true, or even true at the same time, is as unsettling as it is dissatisfying.

Many of these directors, auteurs of the daily, are also workers, but their art does not touch upon their work, instead focusing on their days off in which they have all the time to themselves and which are, supposedly, free of labor, except they are confronted with tasks uncompleted because working requires so much energy and reproduction and, one wonders, whether they consider the filming they do proper labor or if it escapes because it sometimes gives pleasure. The focus on the “day off,” as the title cards for the video often read, suggest the double bind yet again, that these women’s choice of subject-matter is a willful choice, a site of sovereignty, calm, and self-assertion, reminding us, as The Milan Women’s Bookstore Collective wrote decades ago, that even if 90% of my life is not mine, surely the 10% that is gives it all back to me. (The sentence was a declaration and not a question.) but it still seems that work continues in another realm. As much as we may enjoy cooking—well.

These videos, when I discovered them, finding myself suddenly living alone, had filled a void rapidly growing in the absence of more substantial material (is life not substantial?). I had stopped reading books several months prior. I was unable to read a sentence to its conclusion because I could predict how they would begin and end. I knew the words that would be used, the fictional or rhetorical developments that would be made, the thinly veiled preconceptions of the human and political near deadly in their standardization. The only pleasure books could give me was the pleasure of an impeccably timed eyeroll at the predictability of it all. Overall, I think, I was angry, angry at the cliché and repetition of language, the reification of sensation and experience, and when I tried to leave fiction behind for the more objective genres in the land we call nonfiction, that was no help either: I wasn’t predicting character transformations but argumentative moves and moralistic gestures.

Was I going mad? Everyone, everyone trafficked in the same language, phrases, and politics, each book an iteration of the last, nothing new, nothing worthy, because apparently everyone agreed on everything (even when they disagreed fundamentally), I mean, didn’t they all have their punctuation arranged the same and didn’t they use the same narrative layering devices and didn’t they produce the same version of self-hood they had acquired to survive? My cynicism was all-encompassing: where once language had excited and compelled me, it now left me dead, motionless, compulsively consuming that which made me ill, simply because there was no outside and I couldn’t make the outside myself because then I wasn’t operating in language but in nonsense. I once submitted this very essay without punctuation because, I felt, it captured how my mind worked and I thought that was interesting but the editors disagreed so now you have all these little black scars everywhere because apparently it’s impolite to not have them.

Everyone else, after all, uses periods.

It seemed strange that I took solace in these videos made by women, an art form which seemed to reiterate the problems of the books that made me ill: after all, weren’t they just exposing daily life as the site of deadening repetition from which you could never escape (yes). But weren’t there moments beyond the daily labor, even within it, that overwhelmed me in their beauty, like the caring and incisive motion of slicing a cabbage, hands holding it sturdy on the chopping board, the command over a space of one’s own implied in rearranging furniture, the sound of food frying in a pan which, though their food looked nothing like mine, had the potential to invoke those memoire involontaires that made modernism what it was? So many of these videos were records of food made and spaces cleaned, an attention to the absent and disappearing in daily life, a strange aesthetic principle that existed alongside a depressing reminder of how much life has been reduced to its basics, to mere survival. There was an art of living to the arrangement of one’s food on a platter, just for oneself (and one’s million viewers), a kind of ascetic joy to be found in just the basics, a comfort in the routine of keeping oneself alive because what else is there to do?

A question hovered that reflected more about me than it did about these women who occasionally became an object of identification: do these women not read, philosophize, create, have thoughts about their lives, is it all just about these repetitions that feminist writers, from Beauvoir and Ernaux, so easily dismissed as alienating? Watching these vlogs, and asking myself these questions in exasperation over and over again, repetition bore its own fruit: I realized the thinking life cannot be captured by the image because it is a negative, it is precisely what is not there even as it may be animating the images of life these women so carefully curate, yes, that’s right, the intellectual part of our lives is precisely what is not accessible to others, and what cannot be captured. A picture of a book one is reading is not the same as the experience of reading that book, of having the words linger in one’s head for a long time after, similarly, a picture of one at a desk writing does nothing to convey the total life that supports such writing or what happened to enable that dedication to oneself and one’s art form, nor could you adequately capture the effects or remnants the thousands of books read and words written and discarded. (Much like the image of cutting a cabbage is not the same as having cut it.) The image, like the word, cannot show what has been jettisoned, the negative space one has to create to think and dwell and be amid a society that clutters one’s head and home, reducing life to consumable experience and to the products that always leave us wanting more of something that isn’t worth wanting, it is then that I truly see in these videos what is not there, the moments that cannot be symbolized: the intellectual and interior lives that will not rise to the level of the image and, in their rebellion, remain outside the grasp of the social.

Watching this reproductive labor, my cynicism swells again until my hand hovers over the red X at the upper left of my screen. But then! The narrator appears elsewhere, no longer confined within the private as the camera hops to a sunset on the water, sand under our director’s feet, the wind blowing on the speakers, the narrator tells us about a feeling of limitlessness in the world, and I think, yes, how on earth could literature ever stand up to this as a means of recording life, of giving us the will to live, I am enraptured and I believe, in my temporary insanity, that words on the page can give us no sensation of sunset, could not make us hear the wind, it could only approximate these things, truly. Even experiments in language and form, designed to excite that part of your brain that searches for similarity and difference, between language and experience, were repetitions of language, not what was real. The longer I spent submerged in the ocean of image, the farther I drifted from my homeland of surfaces, of black ink on white pages. My face became one with the screen, making me faceless like these women, melding my life into theirs, and it was in this way that I passed an entire day of work and missed my bus.

The day after my disastrous essay attempts and the missed bus, I tried videoing all my actions, with the idea to turn it into a vlog, which, I thought, would be a better version of the novel I was not working on alongside the essay I could not write, since language could only break down motion and thought so far. I wanted to achieve something of the documentarian approach to life these videos suggested, but it was wildly difficult, aiming the camera at every action threw me back into time, every movement Taylorized, broken in its smallest parts to repeated faster and faster, over and over until the gesture reached a stunning perfection at the intersection of speed, efficiency, and ease. None of the takes in these videos that I watched, I realized with a dawning horror as if I were in a film, happen in one go, none of them come out easily and so one must practice even the everyday actions that had seemed so normal and natural but now had turned out to be quite technical and learned. My normal way of cooking was messy and inefficient and would make for a hideous vlog, even leaving aside the fact that the bulb in my kitchen didn’t adequately light the place and part of the kitchen counter was falling off.

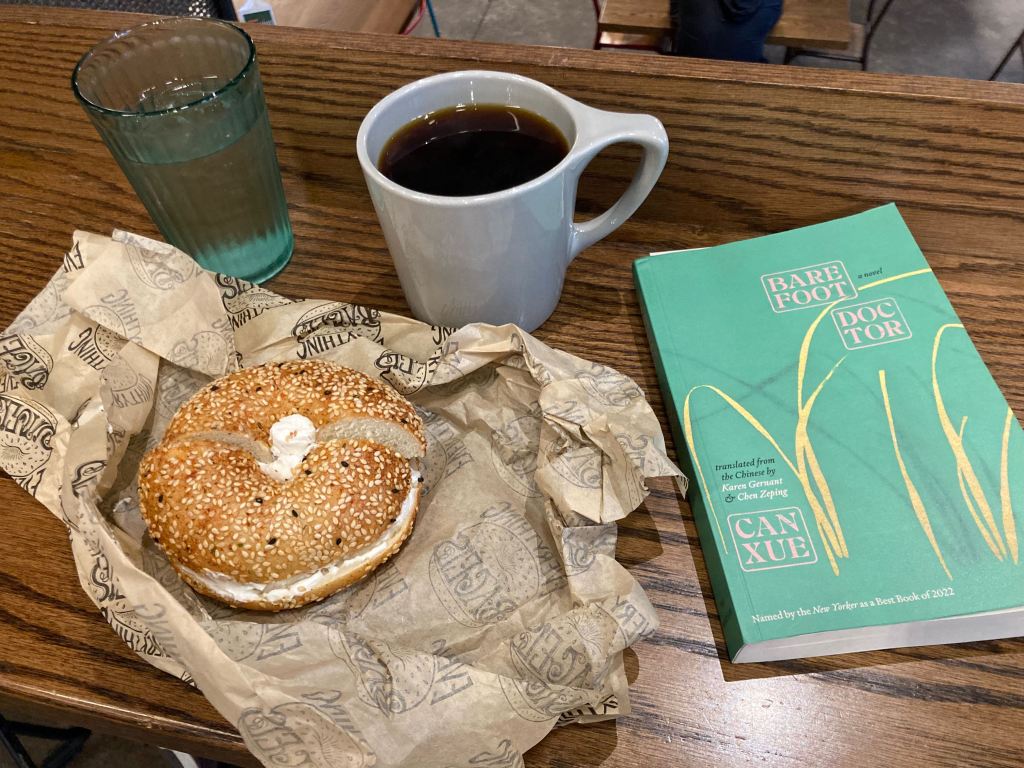

This all came to a head when, on my most precious bagel shop journey (on my day off), I realized that picking up the bagel was not just picking up the bagel, it was interactions with the cashier, gestures to pick the bag up from the counter, a careful checking of the ingredients, an aesthetic shot of said bagel shop, and every action had to be treated this way, so that an hour later I had spent time at the bagel shop simultaneously eating and trying to recreate the experience of eating which produced two realities splitting at the seams. Anyway, an hour later I was exhausted and had wanted a shot of me reentering my apartment, but turning the key in the lock was too difficult as I tried to aim the camera at my hand with the key that my hand kept missing the lock because my attention was split. It was so alienating I became frightened and immediately shut the camera off—it didn’t take me long to realize that creating this blow-by-blow account of a life was unsatisfying for me in its spiritual elements, even if its aesthetic features were somewhat interesting for a viewer.

It wasn’t so simple, I realized. Life in its barest elements was probably not worth representing and I could no longer take refuge in the idea that the image was superior to the word. I knew these two thoughts were irreducibly connected. But how? Anyway the image flattens and deadens as much as language, doesn’t it, it’s not so easy to say that either is better except that one conveys a sense of voice and excess while the other reduces us to what can be perceived visually, the firm lines of the body and the clutter of objects members of the same species in this flattened world. These images present themselves as natural and normal but are neither of those things, and it is this that makes the videos suddenly surreal to me.

No longer could I hide: my fear of language had to be confronted, what it would show me about life, my life? About freedom? I had failed to fully cultivate and sustain my disdain for literature through a traitorous appeal to other art forms and so here I was, exposed, thrown back to my unnatural home in words where the self, split by the social, haunted me (it seemed) with a kinder eye than the grim replication of image and gesture that deviated not at all from reality and yet also existed alongside it. There had to be, I thought, a way of using language so that life could, for a little while, be ignored, and imagination meant that my life did not have to be reduced to its reality, its materiality, to meal cooking and dish washing and apartment cleaning and waiting for days off. I didn’t have to seek a mindless state through the visual capture of day-to-day motions that left me in shards. My mind could be made real and worthy, a subject in its own right, even if only on the page, and even if only briefly, before the dust accumulated and the dishes crusted over. Oblivious to the time passing, I could slip into the ocean of language, surely shark infested, but safe enough for me to submerge and swim, as cunningly as I could to elongate the time before I reached the other shore, floating in waters where, temporarily, the waters suturing my fragmentation.